Government’s Plan to Write Off Sh6 Billion Hustler Fund Debts Faces Scrutiny from Auditor-General

The Government’s proposal to write off over Sh6 billion in unpaid loans from the Hustler Fund, a flagship financial inclusion initiative championed by President William Ruto, has come under intense scrutiny from Auditor-General Nancy Gathungu. In a recent report, Gathungu raised significant concerns about the plan, highlighting unresolved issues in the management and administration of the fund, which was designed to provide affordable financial services to Kenyans at the bottom of the economic pyramid.

The Hustler Fund, launched in 2022 as a cornerstone of Ruto’s campaign promise to empower youth, women, and small-scale entrepreneurs, aims to offer accessible credit, savings, insurance, and investment products through digital platforms like mobile apps and the USSD code *254#. However, the program has been plagued by challenges, including widespread loan defaults and administrative irregularities, which have cast doubts on its sustainability.

According to reports, nearly 10 million Kenyans who borrowed from the fund have defaulted on their loans, with approximately Sh6 billion to Sh6.3 billion at risk of being written off as bad debt. Gathungu’s audit revealed that a significant portion of these borrowers, including an estimated 9 million who accessed small loans as low as Sh500, have become untraceable, further complicating recovery efforts. The Auditor-General emphasized that the decision to write off such a substantial amount requires thorough justification and resolution of underlying issues, including lax oversight and inadequate borrower vetting processes.

The audit also uncovered additional irregularities, such as loans worth Sh31.8 million disbursed to 44,167 underage or unregistered individuals, including some as young as 10 days old, raising serious questions about the fund’s verification mechanisms. Furthermore, loans amounting to Sh681,395 were issued to individuals with future birth dates, ranging from July 2024 to December 2073, pointing to significant flaws in the system’s data integrity.

Lawmakers have echoed Gathungu’s concerns, with some calling for the Hustler Fund to be wound up entirely due to its mismanagement. During a recent parliamentary committee session, Susan Mang’eni, Principal Secretary for Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises, acknowledged the scale of the defaults, noting that while 25.8 million Kenyans are enrolled in the fund, only 9 million are considered reliable borrowers. The government’s request for an additional Sh5 billion to bolster the fund has sparked heated debate, with critics arguing that injecting more funds into a poorly managed program is unsustainable.

“The Hustler Fund was meant to uplift the most vulnerable Kenyans, but we cannot ignore the red flags raised by the Auditor-General,” said a member of the parliamentary committee, who requested anonymity. “Kenyans were lent money, but many have defaulted, and now we’re talking about writing off billions while asking for more funding. This needs a serious overhaul.”

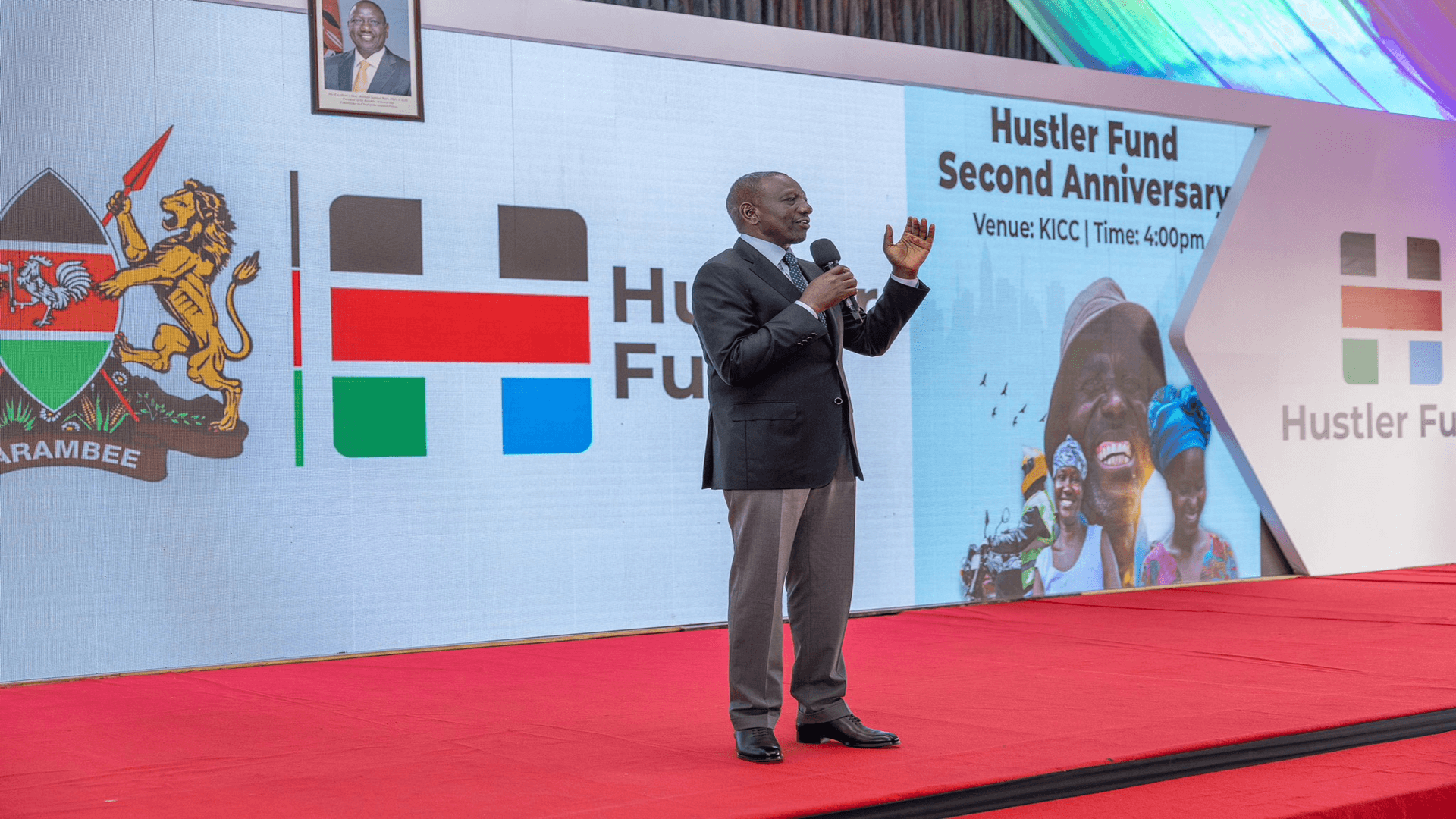

The government has defended the Hustler Fund, emphasizing its role in promoting financial inclusion for millions of Kenyans who lack access to traditional banking services. President Ruto, during the fund’s first anniversary celebrations in Nairobi, described it as a transformative initiative for small-scale traders, youth, and women. However, the mounting defaults and audit findings have fueled public skepticism, with many accusing the government of betraying the very “hustlers” it promised to support.

In response to the defaults, the government has intensified efforts to recover the outstanding loans, including sending notices to borrowers who have defaulted for over a year. There are also plans to tap into M-Pesa and airtime accounts to recover funds, though specific measures for other revolving funds, such as the Uwezo Fund and Women Enterprise Development Fund, remain unclear. Collectively, these funds account for Sh18.4 billion in unpaid loans, with the Hustler Fund alone responsible for Sh7 billion of the total.

The Auditor-General’s report has also drawn attention to broader issues of financial mismanagement in government programs. Previous audits have flagged irregularities in other initiatives, including the Uwezo Fund and the Youth Enterprise Development Fund, where corruption and poor financial oversight have been recurrent challenges. Gathungu’s findings underscore the need for stronger accountability mechanisms to prevent further losses of public funds.

As the government navigates this controversy, the future of the Hustler Fund hangs in the balance. With only Sh1 billion allocated in the upcoming financial year’s budget—far below the Sh6 billion requested—analysts warn that underfunding could further jeopardize the program’s objectives. Public and parliamentary pressure is mounting for the government to address the systemic issues highlighted by the Auditor-General before moving forward with any debt write-offs or additional funding.

For now, the Hustler Fund remains a polarizing initiative, celebrated for its ambition to empower Kenya’s underserved but criticized for its operational shortcomings. As the debate continues, Kenyans await clarity on how the government plans to salvage this key economic program while ensuring accountability for the billions already disbursed.