Blogger’s Death in Nairobi Police Custody Sparks Outrage and Renewed Calls for Prison Reforms

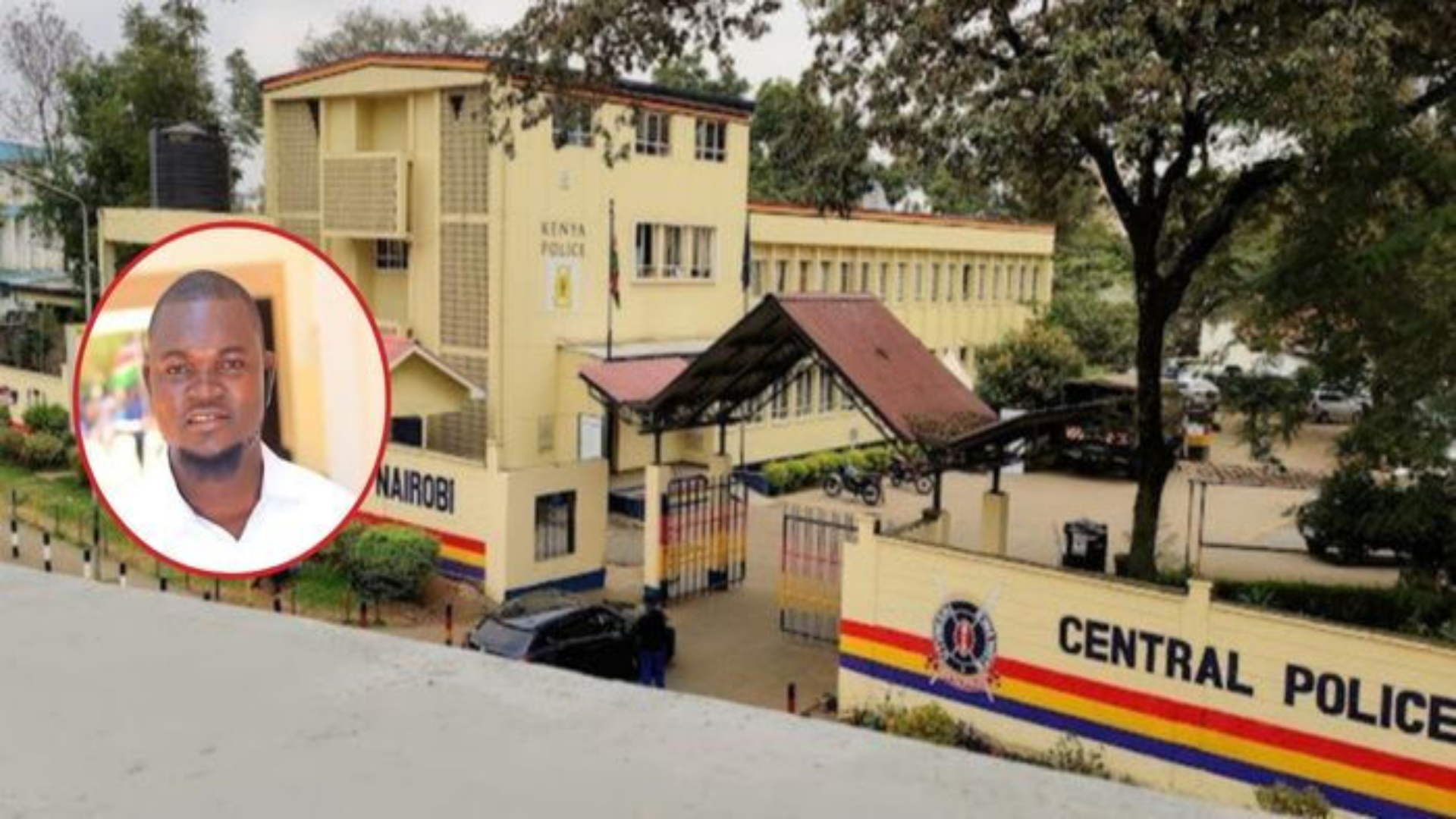

The tragic death of Albert Ojwang, a teacher and social media influencer, in police custody at Nairobi’s Central Police Station has intensified public outrage and brought renewed attention to systemic issues within Kenya’s criminal justice system. Ojwang’s death on June 7, 2025, under suspicious circumstances has led to the interdiction of the station’s Officer Commanding the Station (OCS) and all officers on duty, as ordered by Inspector-General of Police Douglas Kanja. Amid growing demands for justice, proposed prison reforms, including digitization, biometric systems, CCTV surveillance, and alternatives to incarceration, offer potential solutions to address the systemic challenges highlighted by this incident.

Circumstances of Ojwang’s Death

Albert Ojwang, from Homa Bay County, was arrested in Migori on June 7, 2025, for allegedly posting false and insulting information about Deputy Inspector-General of Police Eliud Langat on the social media platform X. He was transported 350 kilometers to Nairobi’s Central Police Station, a move that has been criticized as irregular and unnecessary. According to police, Ojwang died after hitting his head against a cell wall, a claim his father, Meshack Opiyo, and human rights advocates have dismissed as implausible. Opiyo, who traveled to Nairobi after being informed of his son’s arrest, was devastated to learn of his death upon arrival. “They told me he hit his head, but we demand the truth,” Opiyo said at a press conference outside Nairobi Funeral Home on June 8, 2025.

The incident has sparked widespread condemnation, with hashtags like #JusticeForAlbert trending on social media. Civil society groups, including the Law Society of Kenya (LSK) and Haki Africa, have called for an independent investigation, citing a pattern of custodial deaths and disappearances. Hussein Khalid of Haki Africa described the police’s explanation as “unconvincing,” while Amnesty International’s Irungu Houghton labeled the case “shocking” and urged the preservation of evidence, including CCTV footage, to ensure transparency.

Systemic Issues in Kenya’s Criminal Justice System

Ojwang’s death underscores broader challenges within Kenya’s police and prison systems, as outlined in a recent report on prison reforms. The Kenya National Commission on Human Rights (KNCHR) reported 82 abductions and disappearances by March 2025, with 29 individuals still unaccounted for, some believed to have died in custody. Poor record-keeping and lack of transparency exacerbate these issues, making it difficult for families to locate detained relatives and enabling impunity. Overcrowding is another critical problem, with Kenya’s prisons, designed for 34,000 inmates, currently holding over 60,000, resulting in a 284% occupancy rate. Facilities like Nairobi Remand Prison, built in 1911, house nearly 4,000 inmates against a capacity of 1,000, leading to unsanitary conditions, disease outbreaks, and violence.

Inadequate healthcare and violence in detention facilities further compound the crisis. A 2023 report highlighted a 44% vacancy rate in prison mental health staff positions, contributing to suicides and untreated medical conditions. Violence, including torture by officials and inter-inmate conflicts, has led to documented deaths, such as the 2000 King’ong’o prison escape, where autopsies revealed beaten inmates were buried to conceal brutality. Wrongful incarcerations, particularly of petty offenders and vulnerable groups, are also prevalent, with over 40% of Kenya’s 53,000 prisoners being pretrial detainees, some held for years without trial.

Proposed Reforms to Address Systemic Failures

The report on prison reforms in Kenya proposes several measures that could prevent incidents like Ojwang’s death and address systemic deficiencies in the criminal justice system. These reforms focus on enhancing transparency, reducing overcrowding, and upholding human rights:

1. Digitization and Biometric Systems

Implementing digital record-keeping and biometric identification, such as thumbprint readers, can track detainees’ movements, reduce disappearances, and prevent wrongful convictions. A centralized database storing fingerprints and photographs would ensure real-time updates on detainees’ status and location, improving traceability and court efficiency. The India e-Prisons project, which reduced unaccounted detainees by 30% in pilot facilities, serves as a model. However, challenges include high initial costs, data privacy risks, and potential police resistance due to reduced opportunities for bribery. Compliance with Kenya’s Data Protection Act would be essential to mitigate privacy concerns.

2. CCTV Surveillance in Detention Facilities

Installing CCTV cameras in police cells and prisons, particularly in high-risk areas like interrogation rooms, could deter abuse, reduce violence, and provide verifiable evidence for investigations. Footage would be stored for at least 90 days and accessible only by authorized bodies like the Independent Policing Oversight Authority (IPOA). The 2017 video evidence of officer Ahmed Rashid’s killings, which led to his murder charge, demonstrates the value of surveillance. Challenges include privacy concerns, which can be addressed by limiting camera placement to common areas and conducting Data Protection Impact Assessments, as well as high installation costs, which could be offset by partnerships with international organizations like the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. The UK’s prison CCTV systems, which reduced assaults by 15%, highlight the potential benefits when balanced with privacy safeguards.

3. Alternatives to Incarceration for Petty Offenders

Non-custodial measures, such as community service orders (CSOs), probation, and diversion programs, can reduce prison overcrowding and address the overrepresentation of petty offenders. As of March 2023, 7,281 petty offenders were released under CSOs, with 1,068 freed after sentence reviews. Probation allows offenders to maintain jobs and family ties, while diversion programs redirect youth and first-time offenders to counseling or vocational training. These measures lower recidivism by addressing root causes like poverty and lack of education, while also reducing incarceration costs. The Probation and Aftercare Services Department’s training of 234 new officers in 2023 supports the expansion of these programs.

Calls for Accountability and Reform

The interdiction of Central Police Station officers is a step toward accountability, but public skepticism remains due to IPOA’s mixed track record in addressing police misconduct. The LSK and other groups are demanding access to post-mortem reports and CCTV footage to uncover the truth behind Ojwang’s death. The case has also reignited calls for systemic reforms to address the broader issues of police brutality, custodial deaths, and impunity, as seen in cases like the 2016 murders of lawyer Willie Kimani, his client, and their driver, linked to police officers.

Civil society advocates are pushing for mandatory body cameras, stricter detention protocols, and stronger oversight mechanisms to prevent future tragedies. “This is not just about one death. It’s about a system that fails to protect its citizens,” said an LSK representative. For Ojwang’s family, the focus is on justice. “My son was a voice for many,” Meshack Opiyo said. “We will fight until we know what happened and those responsible are held accountable.”

Albert Ojwang’s death has cast a stark light on the urgent need for reform in Kenya’s criminal justice system. The proposed reforms: digitization, CCTV surveillance, and alternatives to incarceration, offer practical solutions to enhance transparency, reduce overcrowding, and uphold human rights. By adopting these measures, Kenya can address the systemic failures that led to this tragedy and build a justice system that prioritizes fairness, accountability, and public safety. As the investigation into Ojwang’s death continues, the nation watches closely, hoping for justice and meaningful change.