Government Not Legally Obligated to Compensate PEV Victims – PS Omollo

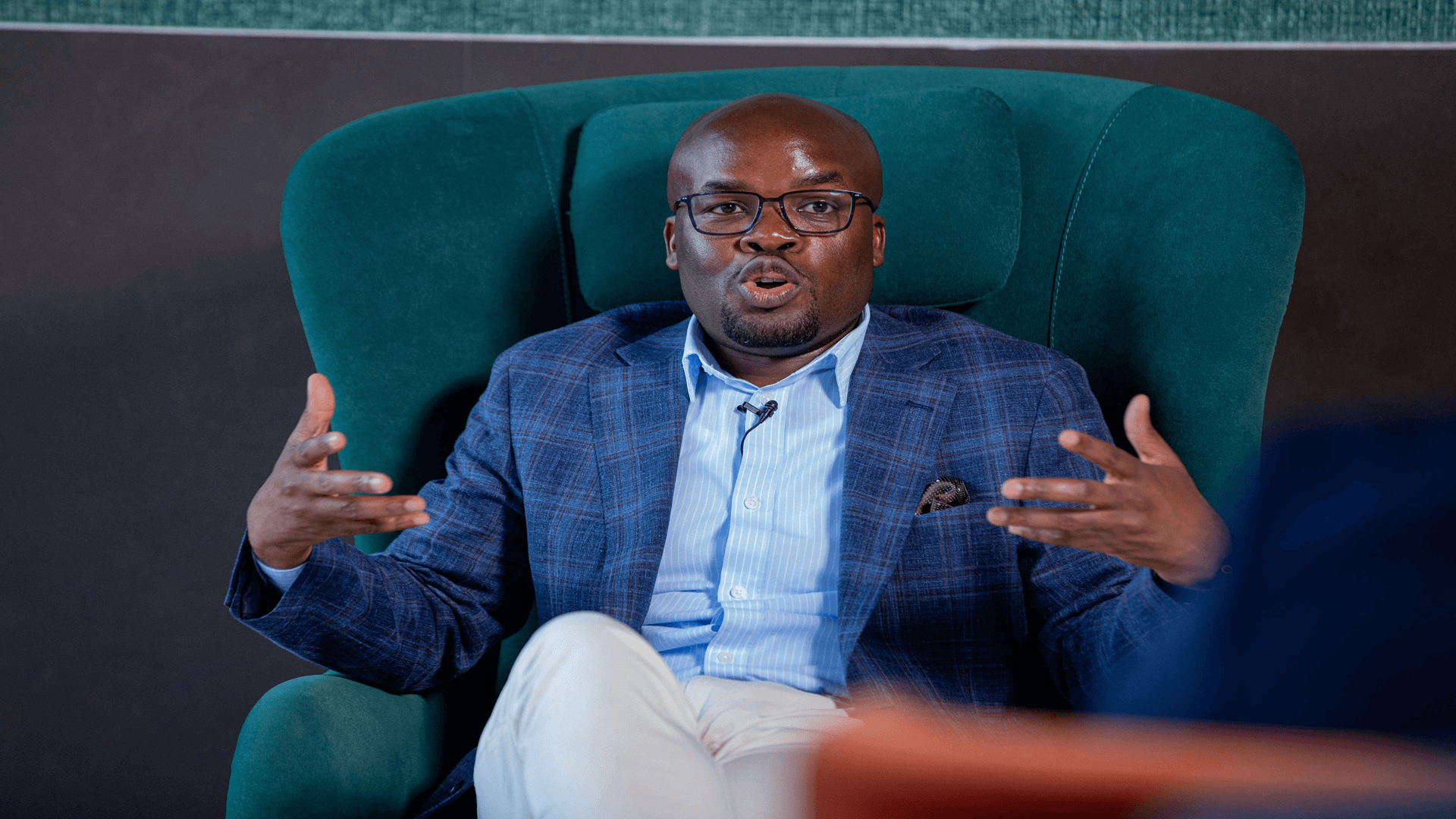

Interior Principal Secretary Dr. Raymond Omollo has stated that the Kenyan government is not legally obligated to compensate victims of the 2007-2008 post-election violence (PEV), sparking debate over the state's responsibility toward those affected by the tragic events. The announcement, made in a recent address, has drawn attention to the unresolved grievances of thousands of Kenyans displaced or harmed during the violence that followed the disputed 2007 presidential election.

Speaking at a public forum, Dr. Omollo emphasized that while the government acknowledges the suffering endured by PEV victims, there is no legal framework mandating compensation. “The government sympathizes with all those who were affected by the post-election violence, but we must clarify that there is no legal obligation binding the state to provide compensation,” Omollo said. He noted that any assistance provided to victims, such as resettlement programs or humanitarian aid, has been on a discretionary basis rather than a legal requirement.

The 2007-2008 PEV, triggered by a disputed presidential election, resulted in over 1,300 deaths and displaced more than 600,000 people across Kenya. The violence, marked by ethnic clashes and widespread destruction of property, remains a painful chapter in the nation’s history. Victims and advocacy groups have long called for comprehensive reparations, including financial compensation, land allocation, and psychosocial support, to address the lasting impacts of the crisis.

Omollo’s remarks come amid ongoing discussions about justice and reconciliation for PEV victims. He pointed to various government initiatives, such as the resettlement of internally displaced persons (IDPs) and the establishment of peacebuilding programs, as evidence of the state’s commitment to supporting affected communities. However, he maintained that these efforts are not driven by legal mandates but by the government’s moral responsibility to foster national healing.

The statement has drawn mixed reactions. Human rights organizations and victim support groups have criticized the government’s position, arguing that it undermines the principles of justice and accountability. “The lack of a legal framework should not be an excuse to deny victims their right to reparations,” said Jane Wambui, a spokesperson for a coalition of PEV survivors. “These families lost homes, loved ones, and livelihoods. The government must take responsibility and create a clear policy for compensation.”

Others, however, argue that the absence of a legal obligation limits the government’s ability to act without parliamentary approval or a structured reparative framework. “The issue of compensation is complex and requires legislation to ensure fairness and transparency,” said political analyst John Mwangi. “Without a legal basis, any attempt at compensation could be challenged in court or lead to accusations of favoritism.”

The debate over PEV compensation has been reignited at a time when Kenya is grappling with broader issues of historical injustices and land disputes. The National Cohesion and Integration Commission (NCIC) has called for dialogue to address the concerns of PEV victims, urging stakeholders to work toward a sustainable solution. Meanwhile, some lawmakers have pledged to push for legislation that would establish a clear framework for compensating victims of political violence.

Dr. Omollo reiterated the government’s commitment to promoting peace and preventing future conflicts, citing ongoing reforms in the security sector and community engagement programs. “Our focus remains on building a united Kenya where such tragedies do not recur,” he said. However, for many PEV victims, the lack of concrete action on compensation continues to fuel feelings of neglect and injustice.

As the nation reflects on its past, the question of how to address the wounds of the 2007-2008 violence remains unresolved, with calls for accountability and reparative justice growing louder.