Nairobi Man Seeks Urgent Court Intervention to Bury Wife and Stillborn Child Held Over Sh2.4 Million Hospital Bill

Nairobi, October 15, 2025 - In a heartbreaking legal battle that underscores the harsh realities faced by low-income families in Kenya's healthcare system, Geoffrey Mende Otiende, a 35-year-old motorcycle courier from Nairobi, has turned to the courts to secure the release of his wife's body and that of their stillborn child. The remains, held by Westlands General and Specialist Hospital and Chiromo Funeral Home, are being withheld due to an outstanding medical bill of Sh2.4 million, despite Otiende having already scraped together more than Sh460,000 from his limited resources. With a planned burial just days away on October 18 in Vihiga County, Otiende's urgent plea highlights a desperate struggle against what he describes as an inhumane practice of using deceased loved ones as leverage for unpaid debts.

The tragedy unfolded about a week before September 29, 2025, when Otiende's wife, Doreen Namubiru, a 32-year-old homemaker, encountered severe complications during childbirth at their modest home in the city's bustling Eastlands area. What began as routine labor quickly escalated into a life-threatening emergency, prompting the couple to rush to the nearest facility equipped for such crises: Westlands General and Specialist Hospital, a private institution known for its advanced intensive care unit nestled in Nairobi's upscale Westlands neighborhood. Namubiru, who was in her late stages of pregnancy with their second child, was admitted immediately and placed under round-the-clock monitoring. Tragically, the baby was delivered stillborn amid the mounting complications, and despite the tireless efforts of the medical team, Namubiru succumbed to her condition on September 29 while still in intensive care. The loss shattered Otiende, who had been by her side throughout the ordeal, holding her hand and praying for a miracle that never came.

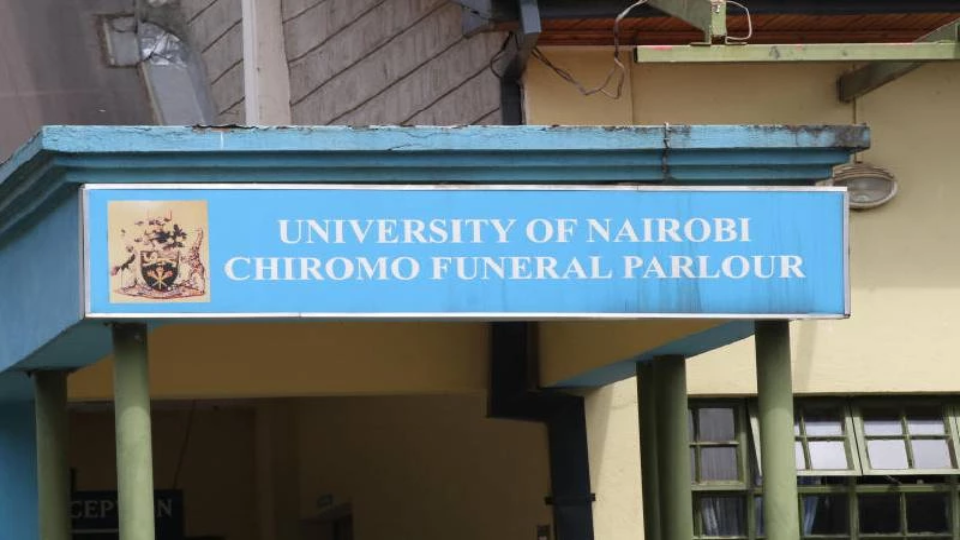

In the immediate aftermath, the hospital transferred Namubiru's body and that of the unnamed stillborn infant to Chiromo Funeral Home, a prominent mortuary in Nairobi that maintains a longstanding partnership with the facility for body preservation and storage. This standard procedure, intended to maintain dignity and prevent decomposition, has instead become a source of prolonged agony for Otiende. Preservation fees continue to accrue daily at the funeral home, adding to his mounting financial burdens at a time when grief should be his only companion.

Otiende, who earns a modest Sh25,000 per month as an independent boda boda rider navigating Nairobi's chaotic traffic to deliver packages and groceries, found himself thrust into an impossible situation. With no comprehensive health insurance and relying solely on his irregular income, he turned to every avenue available: depleting his meager savings account, which held just enough for basic household needs; selling a few personal items like his spare helmet and phone accessories; and humbly approaching friends, extended family, and even former clients for loans. In total, he managed to pay over Sh460,000 toward the bill, a sum that represents nearly two years of his earnings. Yet, the hospital has stood firm, refusing to issue the crucial burial permit or release the bodies until the full Sh2.4 million is settled. This stance, Otiende argues, transforms his profound loss into a punitive standoff, trapping him in a cycle of debt and despair.

Represented by advocate Stephen Liguya of the esteemed law firm Rachier and Amollo LLP, Otiende filed an urgent miscellaneous application at the High Court in Nairobi earlier this week, complete with a certificate of urgency to expedite the hearing. The petition names both Westlands General and Specialist Hospital and Chiromo Funeral Home as respondents, seeking a series of immediate remedies. Primarily, it requests interim orders for the unconditional release of the remains and the burial permit, allowing Otiende to proceed with the funeral rites scheduled for October 18 in his rural hometown of Vihiga County, where family elders and community members await to offer solace and perform traditional Luo ceremonies honoring the departed.

Beyond the immediate relief, the application demands a declarative judgment that the hospital's retention of the bodies constitutes an unlawful act, tantamount to holding human remains as collateral for a commercial debt. Liguya, in his sworn affidavit supporting the case, contends that this practice flies in the face of public policy, ethical medical standards, and fundamental human rights enshrined in Kenya's Constitution, particularly Article 26 on the right to life and dignity even in death, and Article 28 on human dignity. The lawyer emphasizes that no statute empowers healthcare providers to indefinitely detain bodies over unpaid bills, especially when partial payments have been made and no criminal proceedings are involved. Furthermore, Otiende seeks a permanent injunction to bar the respondents from any further interference, including additional preservation charges, pending the full determination of the suit.

Otiende's personal account, detailed in the court papers, paints a vivid picture of a man pushed to the brink. "I wake up every morning with an emptiness that words cannot describe," he states, recounting sleepless nights haunted by memories of Namubiru's final hours and the tiny, lifeless form of their child, whom they had already named in hopeful anticipation. The ongoing detention, he adds, not only inflicts emotional torment but exacerbates his financial woes; with his savings exhausted and loans piling up at exorbitant informal interest rates, he faces the real threat of homelessness for himself and their surviving five-year-old daughter, who now asks innocent questions about her mother's whereabouts. The mounting preservation fees at Chiromo, which can run into thousands of shillings weekly, serve as a cruel reminder that time is eroding both his resolve and his ability to provide closure.

This case arrives at a pivotal moment in Kenya's ongoing discourse on healthcare affordability, where private hospitals often fill gaps left by overburdened public facilities but at a steep cost to vulnerable patients. Critics have long decried the practice of body retention as a draconian debt-collection tactic, with similar stories emerging from facilities across the country, from Mombasa to Kisumu. In recent years, advocacy groups like the Kenya Medical Practitioners and Dentists Union have called for regulatory reforms, including caps on emergency treatment bills and mandatory indigent patient funds, to prevent such tragedies. While the hospital has not issued a public statement on this specific matter, its position aligns with a broader industry rationale: ensuring fiscal sustainability amid rising operational costs for specialized care like the intensive treatment Namubiru received, which involved ventilators, specialized drugs, and a team of neonatologists.

As the High Court prepares to hear arguments, possibly as early as next week, Otiende clings to a fragile hope that justice will prevail, allowing him to lay his family to rest with the dignity they deserve. For now, he continues his daily rides through Nairobi's streets, ferrying strangers' parcels while carrying the unspoken weight of his own unfinished journey home. This story serves as a stark reminder of the human cost behind Kenya's healthcare challenges, urging policymakers and providers to bridge the gap between lifesaving interventions and the compassionate closure that follows.